False Sharing: The Performance Bug You Didn't Know You Had

10 min read

While reading a research paper on the Disruptor library developed by LMAX, I came across the concept of mechanical sympathy and a subtle performance issue called false sharing. The idea that two completely unrelated variables could slow each other down just because they sit too close in memory was fascinating.

That led me down a rabbit hole of how modern CPUs, caches, and memory interact, and how these low-level details can have a surprising impact on high-performance applications.

If you enjoy exploring things under the hood, you're going to love this.

Tell me the basics first

CPU architecture

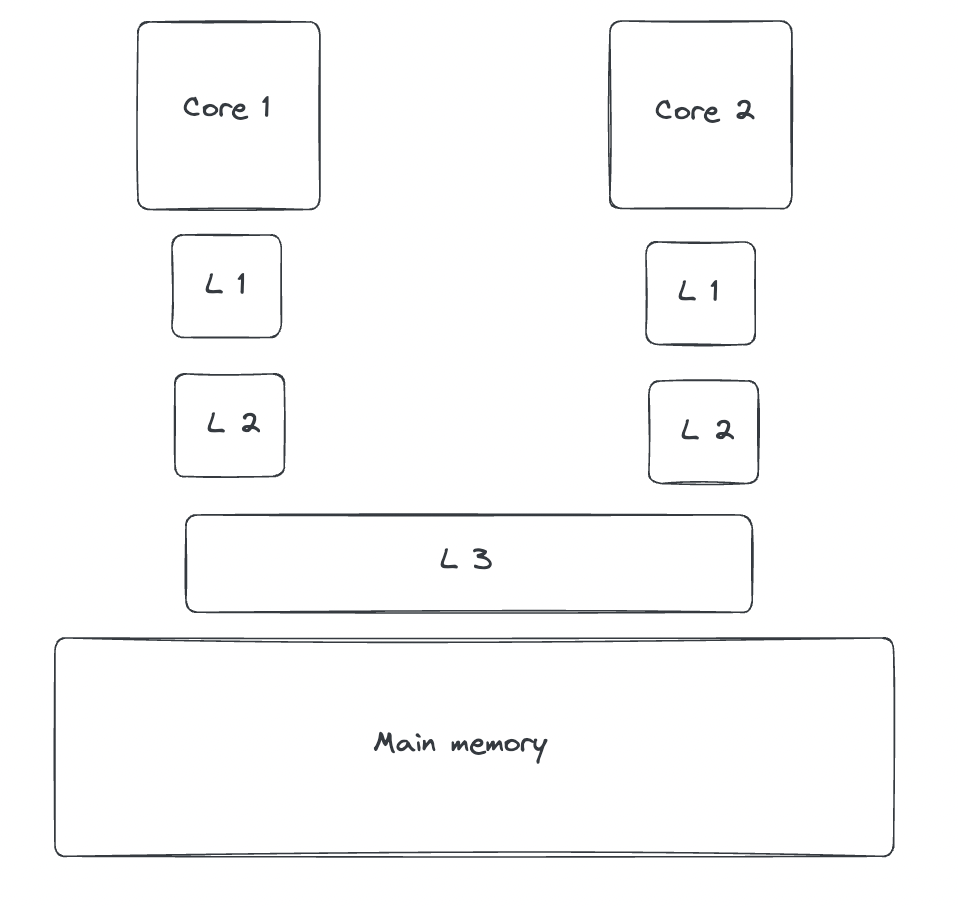

Let's start with a high-level overview of how the CPU interacts with main memory.

The CPU, often referred to as the heart of the system, is responsible for executing instructions, while the main memory (RAM) stores the data and instructions needed for execution. To bridge the speed gap between the fast CPU and slower main memory, modern processors include multiple layers of cache.

Typically, there are three levels of cache between the CPU and main memory: L1, L2, and L3.

The closer the cache is to the CPU core, the faster and smaller it is. L1 and L2 caches are private to each core, while L3 is usually shared across all cores.

When the CPU needs data, it first checks the L1 cache, then L2, followed by L3, and finally, if the data isn't found in any of these, it fetches it from main memory.

MESI (cache coherence protocol)

A single variable from main memory can be loaded into the caches of multiple CPU cores simultaneously. When a thread running on one core modifies that variable, the CPU must ensure cache coherence, which means that no stale copies of the data exist in other cores' caches. To do this, it checks whether the variable exists elsewhere and synchronizes accordingly.

To manage this coherence, modern CPUs use a protocol known as MESI, which classifies each cache line (explained later) into one of four states:

- Modified (M): The data exists only in the current core's cache and has been modified. It differs from the main memory.

- Exclusive (E): The data exists only in the current core's cache and matches the main memory.

- Shared (S): The data may reside in multiple caches and is identical to the main memory.

- Invalid (I): The data is no longer valid. When a core modifies a value in the Modified or Exclusive state, all other caches holding that line mark their copies as Invalid.

Cache line

The smallest unit of data stored in a CPU cache is called a cache line, and its size is typically 64 Bytes.

This means that when the CPU reads data from main memory, it doesn't just fetch the exact variable; it fetches the entire 64-byte block that contains that variable and stores it in the cache.

For data structures stored contiguously in memory, this behavior significantly speeds up operations such as iteration. Since adjacent elements are likely to be on the same cache line or the next one, the CPU can efficiently preload and access them.

However, this optimization can backfire in high-throughput scenarios, particularly when multiple threads are involved.

Consider the following class:

public class Counters {

private volatile long counter1;

private volatile long counter2;

}

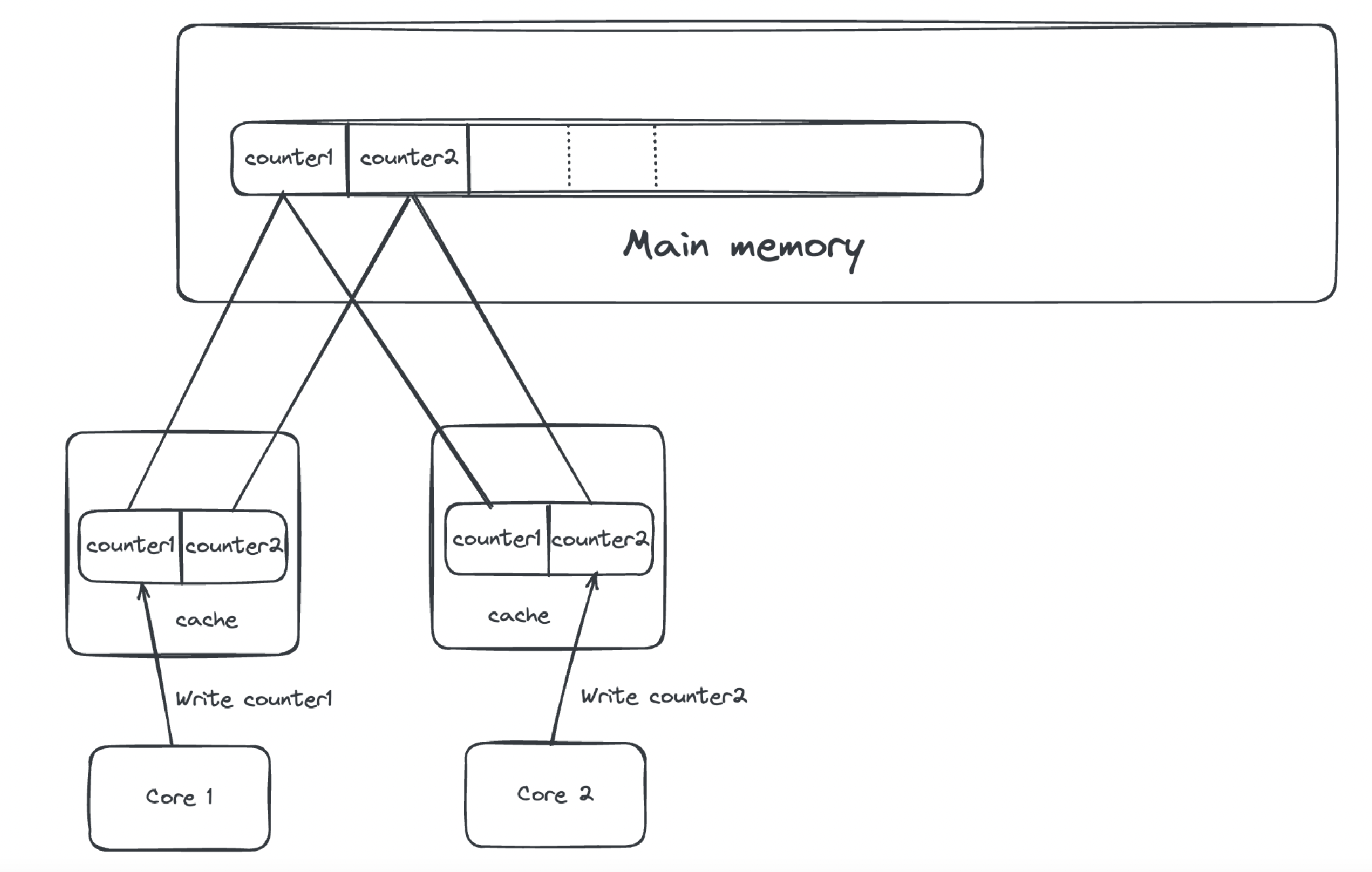

Suppose counter1 and counter2 are independent and are each being updated by separate threads running on different CPU cores. Now, assume these two variables happen to be placed next to each other in memory and thus fall on the same cache line (for simplicity, assume only one level of cache).

Here's what can happen:

- Thread 1 loads

counter1from main memory into its cache line and updates it. - Thread 2 loads

counter2from main memory into its own cache line and updates it.

Even though they're updating different variables, both variables reside on the same cache line, so their actions interfere due to the MESI protocol:

- Now, when Thread 1 tries to update

counter1again, it finds that the cache line has become stale because Thread 2 wrote tocounter2(which shares the same line). This triggers a cache miss, forcing a reload from main memory. - The same thing happens when Thread 2 tries to update

counter2.

This constant invalidation and reloading of the cache line causes a performance-degrading ping-pong effect, even though the variables are independent. This phenomenon is called false sharing.

In effect, it mimics the contention you'd see if both threads were accessing the same variable despite not doing so.

In the next section, we'll look at how LMAX tackled this issue while building a high-performance inter-thread communication library.

Solution to this problem

To address the problem of false sharing, LMAX applied a straightforward but powerful solution: cache line padding.

Knowing that most modern CPUs have a cache line size of 64 bytes, they ensured that frequently accessed independent variables do not share the same cache line.

The idea is to add dummy variables (padding) around the real variables to push them onto separate cache lines. Here's how the padded version of our Counters class would look:

public class Counters {

// Padding to prevent counter1 from sharing a cache line with other variables

private long p1, p2, p3, p4, p5, p6, p7;

private volatile long counter1;

// Padding to separate counter1 and counter2

private long q1, q2, q3, q4, q5, q6, q7;

private volatile long counter2;

// Padding to prevent counter2 from sharing a cache line with other variables

private long r1, r2, r3, r4, r5, r6, r7;

}

This layout ensures that counter1 and counter2 are each isolated on their own cache line, and no other variables unintentionally share cache lines with these high-traffic fields.

This results in no false sharing, no unnecessary cache invalidation, and no performance-degrading ping-pong between cores.

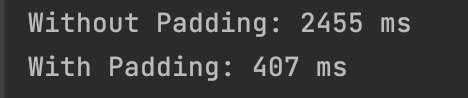

To validate this, I also wrote a quick (and admittedly dirty) benchmark in Java to test the throughput with and without padding, and the results were astonishing.

package org.example;

public class Main {

private static final long ITERATIONS = 100_000_000L;

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

runBenchmark("Without Padding", new NoPaddingContainer());

runBenchmark("With Padding", new PaddedContainer());

}

private static void runBenchmark(String label, Container container) throws InterruptedException {

Thread t1 = new Thread(() -> {

for (long i = 0; i < ITERATIONS; i++) {

container.incrementCounter1();

}

});

Thread t2 = new Thread(() -> {

for (long i = 0; i < ITERATIONS; i++) {

container.incrementCounter2();

}

});

long start = System.nanoTime();

t1.start();

t2.start();

t1.join();

t2.join();

long duration = System.nanoTime() - start;

System.out.printf("%s: %d ms%n", label, duration / 1_000_000);

}

// --- No padding

public static class NoPaddingContainer extends Container {

public volatile long counter1;

public volatile long counter2;

@Override

public void incrementCounter1() {

counter1++;

}

@Override

public void incrementCounter2() {

counter2++;

}

}

// --- With padding to avoid false sharing

public static class PaddedContainer extends Container {

private long p1, p2, p3, p4, p5, p6, p7; // cache line padding

private volatile long counter1;

private long q1, q2, q3, q4, q5, q6, q7; // cache line padding

private volatile long counter2;

private long r1, r2, r3, r4, r5, r6, r7; // cache line padding

@Override

public void incrementCounter1() {

counter1++;

}

@Override

public void incrementCounter2() {

counter2++;

}

}

public static abstract class Container {

public abstract void incrementCounter1();

public abstract void incrementCounter2();

}

}

And the result was almost 6x faster.

Ending notes

Sometimes, it's the low-level details that make the biggest difference in how software performs. The problem of false sharing is a great example of how understanding what's happening under the hood can lead to significant performance gains.

While this issue is most relevant in high-throughput, low-latency systems, like those built by financial firms, where even nanoseconds matter, it's still a fascinating insight for any engineer who wants to write performant, scalable software.

I encourage curious readers to dive deeper using the resources shared below. Even if you don't encounter false sharing in your day-to-day work, understanding how and why it happens can make you a better systems thinker, and that's always valuable.

https://trishagee.com/2011/07/22/dissecting_the_disruptor_why_its_so_fast_part_two__magic_cache_line_padding/

https://strogiyotec.github.io/pages/posts/volatile.html

https://mechanical-sympathy.blogspot.com/2011/07/false-sharing.html

Thank you for reading. Hope you learned something new today.

I also share the research papers I read on my blog with a high-level gist of each. Check it out here.