InnoDB Doesn’t Use a Regular LRU Cache — Here’s Its Secret

6 min read

While reading Database Internals, I discovered that database engines often cache recently accessed pages of index and data files in memory. This speeds up not just reads, but writes too.

That got me curious about how InnoDB does it -- and it turns out, it's far from a basic LRU cache. InnoDB adds a smart twist that makes its buffer pool resistant to full table scans and short-lived page accesses that otherwise pollute the cache.

In this article, I'll walk through how InnoDB's buffer pool works under the hood, how it improves on traditional LRU, and how you can tune it for better performance. If you enjoy exploring the internals of real-world systems, this one's for you.

What's a buffer pool (a quick refresher)?

The buffer pool is InnoDB's in-memory cache. It stores frequently accessed pages from your database files -- both index and data pages.

It serves two major performance goals:

- Speeding up reads: If a requested page is already in memory, there's no need to read it from disk.

- Optimizing writes: When you write data, it's first stored in the buffer pool and later flushed to disk in batches. This reduces disk I/O and improves throughput.

Behind the scenes, this pool is managed by a cache eviction strategy, which is a variant of LRU.

How basic LRU works (and why it fails)?

A traditional LRU cache uses two data structures:

- A hash map that maps keys (like page IDs) to nodes. Each node contains the actual page data.

- A doubly linked list to track usage order. When a page is accessed, its node is moved to the head of the list. The least recently used pages drift toward the tail.

When the cache is full, pages near the tail (least recently used) are evicted first.

This works well in many systems, but not for databases.

The problem: cache pollution

Let's say someone runs a full table scan by mistake. Suddenly, hundreds of pages that may never be accessed again flood the buffer pool. In basic LRU, each newly accessed page goes to the head of the list, pushing older, more useful "hot" pages toward eviction.

Another case is read-ahead. InnoDB detects sequential access patterns (for example, range queries) and prefetches nearby pages. But if you're running an ad hoc analytical query once a day, those prefetched pages will still take up cache space even if they're never touched again.

So, how do we prevent these one-time-use pages from evicting frequently used ones? -- Let's see in the next section.

Innodb's solution: Midpoint insertion LRU

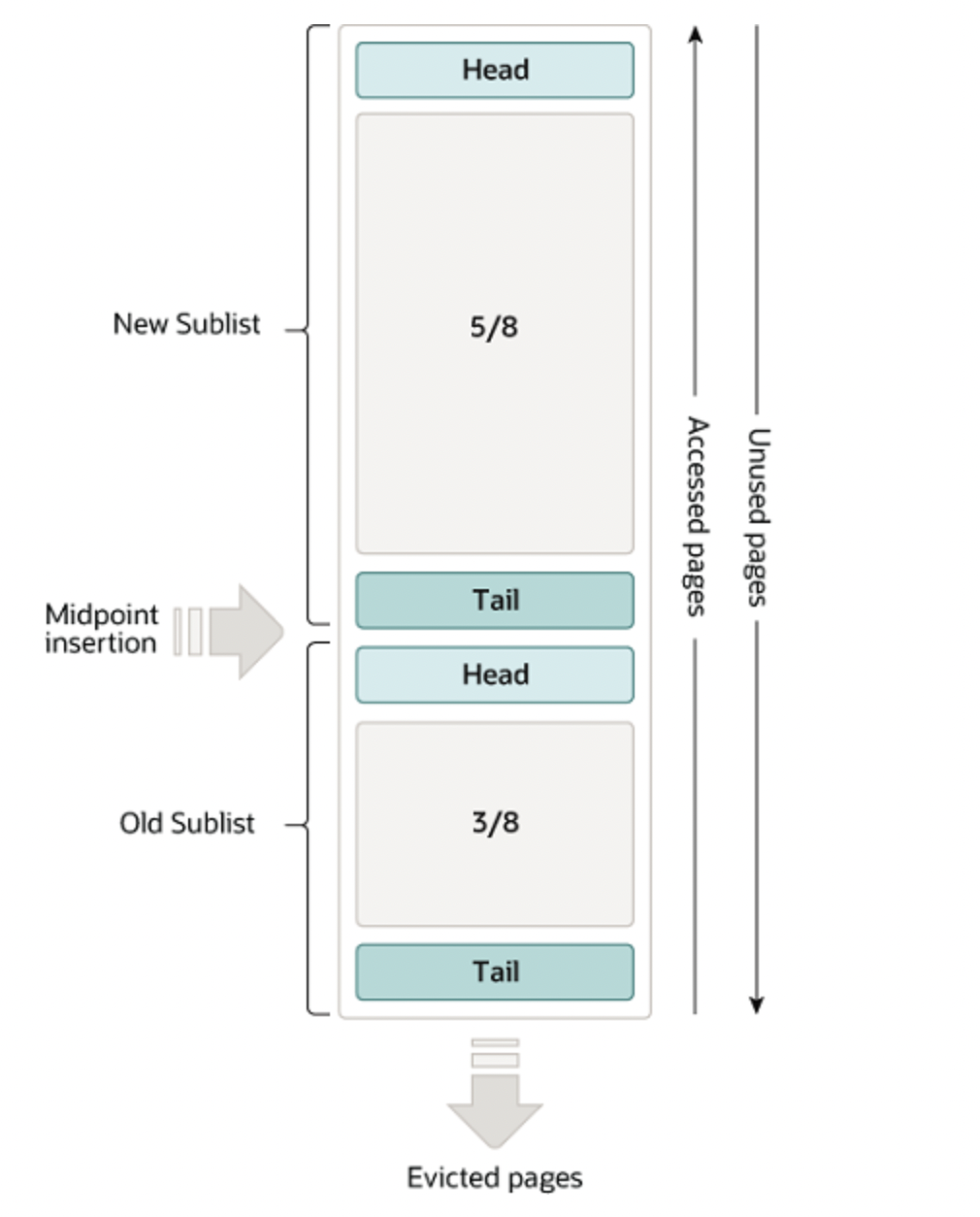

InnoDB solves this problem using a midpoint insertion strategy, splitting the LRU list into two logical regions:

- Old region (by default, 37% of the buffer pool)

- New region (the remaining 63%)

Refer to the image below to see how it looks:

Instead of inserting new pages at the head of the list, InnoDB places them somewhere in the middle, in a region known as the old region. This region starts at a configurable point in the LRU list. By default, at the 3/8th mark, set via the innodb_old_blocks_pct parameter.

Pages in the old region are considered cold and are eligible for eviction unless they prove themselves.

Only if the page is accessed again after a short delay is it moved to the new region, where it's treated as hot and protected from eviction. This delay is controlled by the innodb_old_blocks_time setting (default: 1000 milliseconds).

How this helps

This change is surprisingly effective:

- Pages accessed only once (like during table scans or prefetches) die in the old region without polluting the hot cache.

- Pages accessed repeatedly over time migrate to the new region and stay cached.

In other words, InnoDB rewards sustained relevance, not short-term bursts.

Ending notes

Before diving into this, I assumed InnoDB used a plain LRU cache, nothing fancy. But digging into the details changed my perspective.

What looks like a minor implementation detail has a huge impact on real-world database behavior.

Understanding this helped me appreciate how much thought goes into storage engine design. I hope it helped you too. I encourage curious readers to go through the following references to know more about the same.

References:

https://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/8.4/en/innodb-buffer-pool.html

https://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/8.4/en/innodb-performance-midpoint_insertion.html

https://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/8.0/en/innodb-disk-io.html

https://www.alibabacloud.com/blog/an-in-depth-analysis-of-buffer-pool-in-innodb_601216

Thank you for reading.

I regularly read a wide range of technical books and share my learnings here, whether it's database internals, system design, or just clever engineering ideas. Feel free to explore the rest of the blogs if that sounds interesting to you.

Thank you for reading.

Happy coding!