Disruptor: High performance alternative to bounded queues for exchanging data between concurrent threads

11 min read

These are just high-level notes to give you a quick overview. For the full details, read the complete research paper here

Introduction

The Disruptor was originally designed to efficiently pass data between different stages of a processing pipeline. Traditional queues were too slow for this purpose. Data exchange using them could be as slow as accessing data from disk, which becomes a bottleneck in high-performance systems.

A key concept discussed in the Disruptor research paper is mechanical sympathy. This refers to designing software with a deep understanding of how modern CPUs work so that the software can run as efficiently as possible.

Disruptor can handle over 25 million messages per second, with latency as low as 50 nanoseconds on processors running at moderate clock speeds. This performance is extremely close to the theoretical limits of core-to-core communication on modern CPUs.

The complexities of concurrency

Concurrent execution revolves around two core challenges: mutual exclusion and visibility of changes.

- Mutual exclusion ensures that when multiple threads access a shared resource, only one can modify it at a time—preventing race conditions and data corruption.

- Visibility of changes deals with ensuring that when one thread updates a shared value, other threads can reliably see the updated value.

Among all operations in a concurrent system, contended writes are the most expensive. Coordinating these writes requires heavy synchronization, which can significantly degrade performance.

The cost of locks

Locks provide mutual exclusion and ensure that the visibility of change occurs in an ordered manner. But, locks are expensive because they require arbitration (thread coordination) when contented.

The arbitration is achieved by a context switch to the OS. While the OS has control, OS may choose to do other housekeeping stuff. Additionally, the previously cached data and instructions (in the CPU cache) could be invalidated by another thread when the context switch happens.

The cost of CAS

A CAS operation is a special machine-code instruction that allows a word in memory to be conditionally set as an atomic operation. Example, increment a counter if it is currently 5.

While updating, if the value doesn't match, then it is up to the thread attempting to perform the change to retry, re-reading the counter incrementing from that value and so on until the change succeeds.

This approach is significantly better than the locks because it doesn't need a context switch.

However CAS operations are not free of cost. The reasons for the same are explained below:

- CAS needs to make sure no other thread can interfere mid-operation so the CPU blocks it's instructions pipeline. This lock is brief but impacts performance.

- After a thread successfully performs a CAS, other threads need to see the updated value right away. This requires a memory barrier (explained better in the next section), which is an expensive operation that ensures all previous writes are visible to other threads before the CAS operation completes. This also prevents instructions re-ordering optimisation of CPU.

Memory barriers

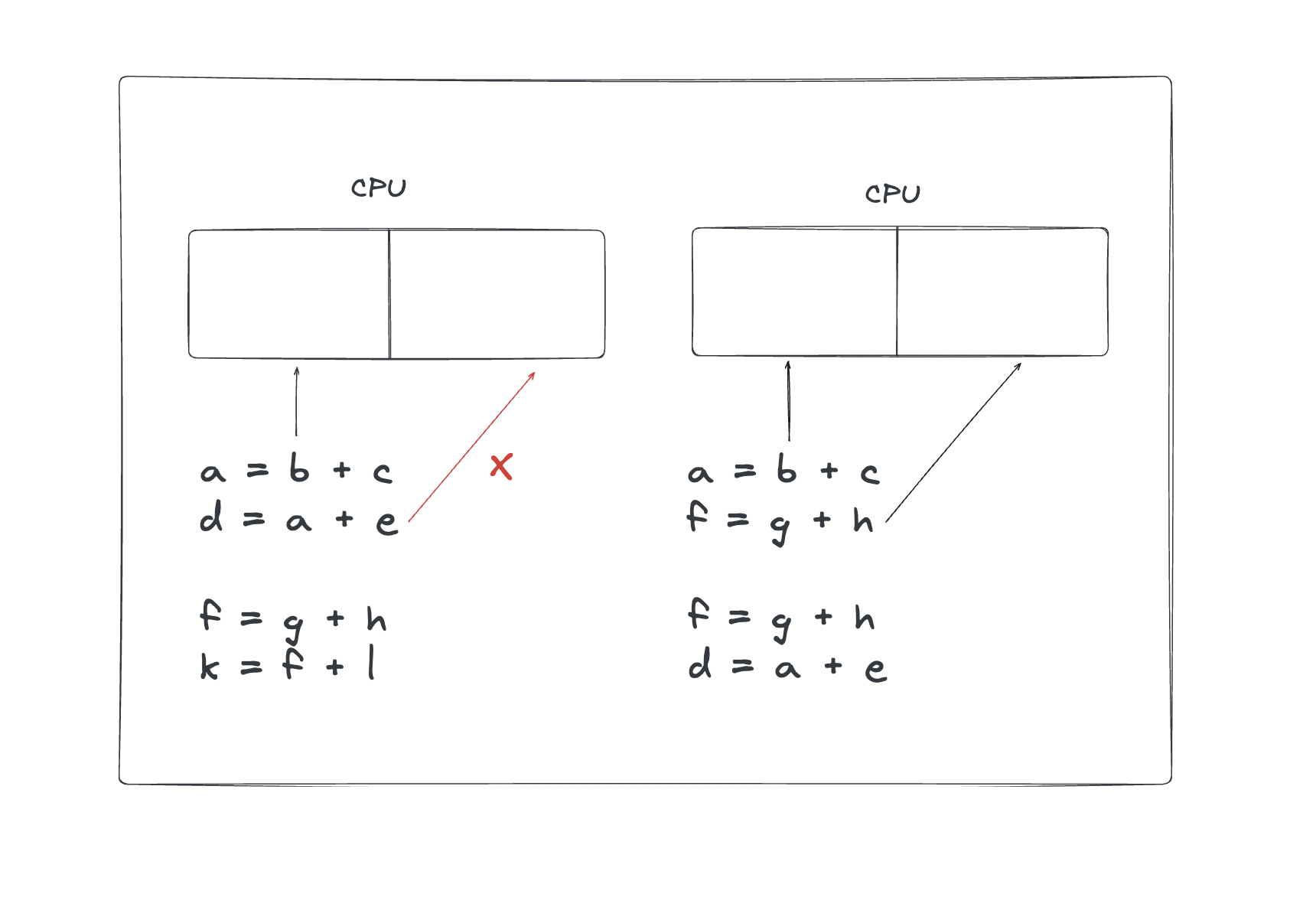

Modern processors perform out-of-order execution of instructions to improve performance. An example for the same is given below:

Here, a = b + c and d = a + e cannot execute in parallel because the second instruction depends on the first one. This is also true for the other set of instruction f = g + h and k = f + l.

But, a = b + c and f = g + h can be executed in parallel. This is called out-of-order execution.

And it works for single-threaded programs because the processors need only guarantee that program logic produces the same results regardless of execution order.

However, this can lead to issues in a multithreaded environment. When threads share data, it is important that all memory changes appear in order, at the point required, for the data exchange to be successful. Let's look at the example below to understand this better:

// Thread 1

data = 42; // (1)

ready = true; // (2)

// Thread 2

if (ready) {

System.out.println(data); // (3)

}

Here’s what we expect:

- Thread 1 sets data to 42, then sets ready to true.

- Thread 2 sees ready == true and prints data, which should be 42.

But, if the instructions are executed out-of-order, then Thread 2 might see ready as true before Thread 1 has set data to 42. This could lead to Thread 2 printing an incorrect value.

To solve this problem, processors use memory barriers. A memory barrier is a special instruction that prevents the CPU from reordering instructions across the barrier. It also ensures that all previous writes are visible to other threads before any subsequent reads or writes.

Cache lines

A cache line is the smallest unit of memory that a modern CPU reads from or writes to its cache. It is typically 64 bytes in size.

If two variables are in the same cache line, and they are written to by different threads, then they present the same problems of write contention as if they were a single variable. This is a concept know as false sharing. For high performance then, it is important to ensure that independent, but concurrently written variables do not share the same cache-line if contention is to be minimised.

The problem of queues

Queue implementations often suffer from write contention on shared variables like the head, tail, and size. In practice, queues are rarely in a steady state where the producer and consumer operate at exactly the same rate. Instead, they tend to swing between being nearly full or nearly empty, depending on which side is faster.

Even if the head and tail operations are managed using separate synchronization primitives like CAS, they frequently reside on the same cache line. This causes false sharing, where independent updates from producer and consumer threads unintentionally interfere due to shared cache hardware, leading to performance degradation.

The design of the LMAX disruptor

At the heart of the disruptor mechanism sits a pre-allocated bounded data structure in the form of a ring-buffer. Data is added to the ring buffer through one or more producers and processed by one or more consumers.

Memory allocation

The ring buffer pre-allocates all its memory during startup. This eliminates problems related to garbage collection in managed languages, as the same entries are reused throughout the lifetime of the Disruptor instance.

Since the entries are allocated together at initialization, they are highly likely to be placed contiguously in main memory. This layout promotes cache-friendly access patterns like cache striding, improving performance by minimizing cache misses.

Teasing apart the concerns

A pre-allocated ring buffer is used to reduce the load on garbage collector. This also helps in certain CPU optimisations like cache striding since it is likely that the entries are placed contiguously in memory.

Before adding the data into this buffer, a sequence number is assigned to each entry. This sequence number is used to determine the position of the entry in the ring buffer. On most processors there is a very high cost for the remainder calculation on the sequence number, which determines the slot in the ring. This cost can be greatly reduced by making the ring size a power of 2. A bit mask of size minus one can be used to perform the remainder operation efficiently.

In most common usages of the Disruptor there is usually only one producer. Typical producers are file readers or network listeners. In cases where there is a single producer there is no contention on sequence/entry allocation.

In cases where multiple producers are involved, producers will race one another to claim the next entry in the ring buffer. This is supported by a CAS operation. Then, they write their data into the assigned slot and commit the offset so that it becomes available to the consumers.

Sequencing

Sequencing is the core of concurrency in the Disruptor. Producers claim the next sequence number to write data into the ring buffer. Single producer can use a counter; multiple producers use CAS to claim sequences atomically.

Once data is written, the producer busy-spins waiting for previous sequences to be committed, then updates the cursor to commit its own sequence. This makes the data visible to consumers.

Consumers use memory barriers to wait for a sequence. Once cursor is updated, memory visibility guarantees safe reads. Each consumer maintains its own sequence to prevent the ring from wrapping and to coordinate orderly processing.

With one producer, no locks or CAS are needed—just memory barriers.

Batching effect

When consumers are waiting on an advancing cursor sequence in the ring buffer an interesting opportunity arises that is not possible with queues. If the consumer finds the ring buffer cursor has advanced a number of steps since it last checked it can process up to that sequence without getting involved in the concurrency mechanisms

Dependency graphs

Rather than using multiple queues to process data in a pipeline, Disruptor uses a single ring buffer that could be consumed by multiple consumers. This results in greatly reduced fixed costs of execution thus increasing throughput while reducing latency.

This summary highlights the key ideas from the Disruptor paper. While the concepts remain influential, some implementation details may differ in newer versions. For the most accurate and up-to-date usage, refer to the official Disruptor documentation.

To dive deeper, you can read the full paper here.